Lane Changer — Safiya Randera, lanes that cross land, community, and art

Weston, where I live, is lucky to have lane-changer, Safiya Randera, in its midst. Safiya is the driving force behind things like the Creative Commons Collective Artist Supper Club and the green sanctuary nestled between a high-rise and a parking lot. But she wouldn’t be in this series if she hadn’t had some significant shifts to get here.

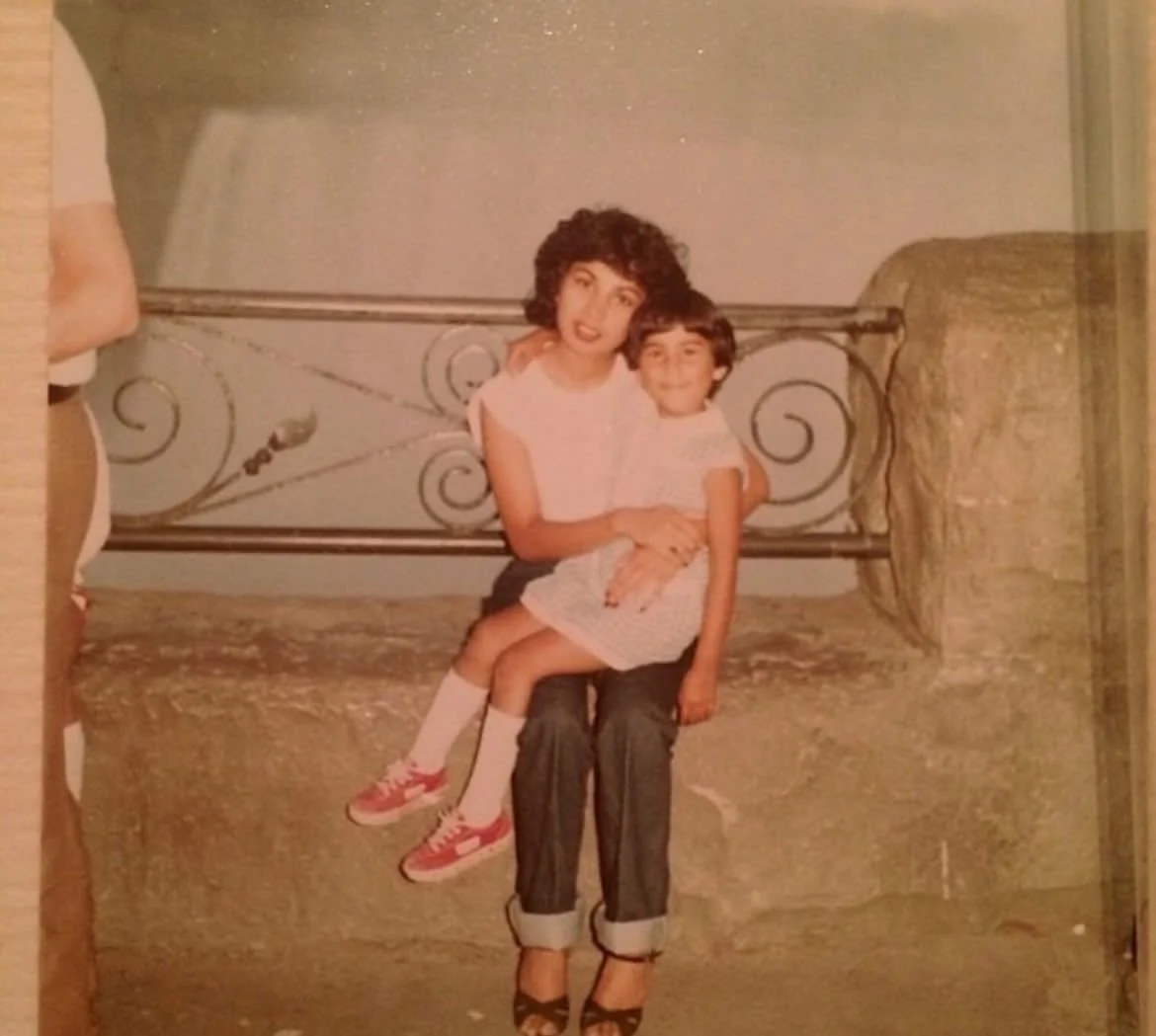

Randera was born in the UK 52 years ago and arrived in Canada three years later, the youngest of three daughters of a Malawian mother and a Gujarati father. She left the family home in Brampton for the Ontario College of Art and Design (OCAD), expecting a future as a visual artist. In third year, she studied for a term in Italy. That Christmas, Italian TV was full of footage from the Siege of Sarajevo. Despite having no experience with war or emergency aid, 22-year-old Safiya felt called to do something. The Red Cross said ‘no thanks’ to her offer. She went anyway, phoning her mother back home from Sarajevo on New Year’s Eve. This was her first lane change and the first significant example of her fierce spirit that fuels her need to improve others’ lives and achieve justice.

Safiya returned to OCAD for her final year, shifting from painting and drawing to experimental filmmaking. Her film, Jangri, won the Audience Choice Award Best Short Film, at Toronto’s 1998 Inside Out, a festival for films made by and about 2SLGBTQ+ people of all ages, races and abilities. This launched Safiya into the film lane — she worked on film sets to make money while making her own on the side. She describes that version of herself as a ‘bit of a player,’ complete with Jeep-driving and dating all the right women.

At age 27, back injuries sustained in a car accident sidelined her from work, putting her into a rehab hospital for six months. She refocussed her work again from set-work to film editing, something she could do from the wheelchair she used for 18 months while her body healed enough to walk again.

Then 9/11. Randera’s Muslim faith together with her queer identity have always been central to her artistic output. Suddenly the fact of her father’s senior role at their Brampton mosque made her fear for his safety. That prompted her 2010 short doc, My Father, the Terrorist?, which she describes as a contemplation on civil liberties, racism, and the politics of secret intelligence in Canada.

Thirteen years ago, though, Safiya Randera started on a healing journey that defines the person I know. It began with her mother’s death just four months after her diagnosis. She was just in her late 50s. The night after her Islamic burial was a terrifying one for Safiya. In the morning, a Shaman provided her comfort by saying he’d accompanied her mother to the light. Safiya had a newfound interest in psychopomps, those responsible for escorting newly deceased souls from earth to the afterlife. For two years, she traveled back and forth to a learning centre in the Amazon. In exchange for film-making for the centre, she had access to sessions.

Cancer deaths often prompt lane changes — certainly that’s true for me. Safiya’s mother’s death resulted in Safiya finding a new lane as a psychopomp with a healing practice. The emotional toll of the work however affected her physical health.

By 2020, illness had her bedridden. Fed up with western medical practitioners who identified her serious health issues as an autoimmune disorder, Safiya sought the help of Malidoma Patrice Somé, a writer and workshop leader in the field of spirituality. Through a divination on March 14, 2020, Somé recommended she join him at his home base in Burkina Faso to be healed. The very next day, COVID lockdowns restricted international travel. By August, she found a way to get to Africa where divinations from three elders gave her remedies. Within a month, she returned to Canada, healed, and having received the great and unusual honour of being initiated into a West African Shamanic tradition as a stick diviner.

Randera began life in a new lane traveling by van across North America offering ceremony and divination, including as the head of the healing village at a multi-day celebration of women remembering and practising basic human skills to ensure the survival of the body and the soul. This rebirth as a healer had some in her previous film life confused and also is haram within her Muslim faith. But she wasn’t daunted by that.

Two years ago, Safiya realized she was no longer interested in “serving white women in yoga pants” who sought healing but remained silent on the Gazan genocide. She returned to Toronto full-time. It’s hard to know what to do to help Gaza so she shares stories on her social media and supports the Palestinian community and rallies here in Toronto. Reminiscent of her trip to Sarajevo two decades earlier, she joined several thousand others from around the globe in Cairo earlier this year for the Global March to Gaza. Regrettably, the march was called off after the Egyptians detained several hundred of the marchers. I joined her many friends and family in a collective sigh of relief when Safiya returned safely.

Now Safiya’s all about making meaningful connections for herself and others, from the home she shares with Owen, her Brussels Griffon dog, in Weston Commons, a community of 26 affordable live-work artists units opened in 2019 by the now-defunct Toronto Artscape. I first learned of her through her immersive experience art, Space Mosque, part of Toronto’s 2024 overnight art festival, Nuit Blanche. By the end of December, she, along with the head of Crossroads Theatre, had started the monthly pot-luck dinners, and this summer, she opened the Creative Commons garden adjacent to the building where she and her fellow artists live. Randera’s community animation will always be done in right relation to the land, reflecting our interconnectedness with each other and with our physical environment. To that end, the opening of the garden included words from a local Indigenous elder; growing in the garden is Indigenous tobacco, a grapevine planted by a displaced Palestinian living in Weston, and tomatoes planted from seeds handed down by another community-member’s grandfather.

It’s nearly universal — lane changers have no regrets about their shifts. Safiya’s no different. Well, she does regret not keeping up with her painting. That’s the next lane change she’s planning — a shift back to painting. But at just 52, I bet she’s got even more lanes ahead.

As we finished our lunch, I asked Safiya why she takes the risks she takes. “I’m not afraid. I know I’m here to make good trouble.” I’m just grateful there are lane changers like Safiya.

For more about Safiya, check out her website at: https://www.safiyarandera.com

Missed previous Lane Changer profiles?

Peter Chandler, how it all began for me

Cathy Crowe, her lane is the street

Marissa Bastidas, same lane, new direction

Pam Hudak, living on a multi-lane highway

Jennifer, crossing lanes from Phuket to pup-minderEmma Simpson, from taxiway to writing terminal

Jessica Waraich, changing lanes on the career on-ramp

Michelle Simmons, straddling two lanes in her mid-40s

Sybil Chandler (1928-2025), proud to find life’s off-ramp

Faiv Noelle, solo on a global highway

Karly Wilson, waiting aside life’s highway for the next lane

Marya Williams, when life’s lanes bring you full circle

Carolyn Whitzman, lanes inspired by mother and grandmotherValerie Groves, when the lane is bordered by perennials and pollinatorsElana Harte, Changing lanes on the “Being of Service” HighwayFaren Bogach, the fast lanes of lawyering

Cathy Mann, finding the lane to Nova ScotiaDenese Gascho, finding common ground in different lanes

If you like what you’re reading, there is no greater compliment than to become a subscriber. Sign up below with your email address to receive an email with my weekly blog.